[Updated]

Since the end of the Civil War, the thing most likely to incite white violence against emancipated Black citizens was their success. Giving Black Americans full rights, beyond the freedom that had so grudgingly been granted to them after the Union prevailed, proved to be a bridge too far for many whites—even Northern Republicans. Any steps Black Americans took to avail themselves of those rights often triggered swift and severe reprisals. In retrospect, it seems self-evident that the driver behind the essential re-enslavement of Black people after Reconstruction was Black prosperity.

The establishment of Black communities, organized by churches, benevolent societies, schools, and, most significantly, political organizations, resulted in real electoral power that threatened the Southern ideal of white supremacy. While Blacks understood the power of achieving literacy, whites understood the threat that literacy posed. Disrupting the spread of knowledge among the Black community became an important tactic in reestablishing and maintaining the antebellum white social order in the postwar South.

Because literacy rates were so low, educated Blacks often served in more than one leadership role. As social psychologist Susan Opotow writes, “Violence by terrorist groups limited the ability of the black community to sustain an influential presence in Southern decision-making institutions, destroying a political and social movement by targeting the intelligentsia.” This strategy was called sophiacide: literally, the “killing of knowledge.”

Black prosperity was punished with relentless savagery. When Black soldiers returned home after World War I and World War II wearing the uniforms of the American armed forces, they were treated like a threat to the established racial hierarchy. While Black veterans expected that having served would confer on them a certain respect back home, white people interpreted that expectation as arrogance. That a Black man would think himself equal to a white man could not be allowed to stand—especially in the American South. Black veterans were beaten and sometimes lynched, their uniforms a visible reminder of their claim to equality and an implicit rebuke to the white man’s false sense of superiority.

Black Americans had to try ten times as hard to achieve one-tenth as much, and Black people’s success—even in the face of the obstacles placed before them—was the greatest offense against white supremacy. It was also the most dangerous challenge to it.

Mostly through violence, but also through legislative means, whites impeded, undermined, and reversed Black advancement with complete impunity. Law enforcement either looked the other way or was directly involved in attempts to thwart the rights of Black citizens.

The 1921 massacre in Tulsa, Oklahoma, which has been referred to as the nadir of race relations in America, was a direct result of the white supremacist hatred of Black success. O. W. Gurley, a wealthy Black American from Alabama, established Greenwood in 1906. Fifteen years later, it was a thriving, predominantly Black section of Tulsa with over ten thousand residents. Booker T. Washington dubbed it “Negro Wall Street” because of its successful businesses and affluent inhabitants.

As Greenwood became more prosperous and populous, however, tensions with the neighboring white population simmered. On May 31, 1921, white citizens finally found an excuse to retaliate when Dick Rowland, a nineteen-year-old Black man, entered an elevator in a downtown office building and had a fateful interaction with, Sarah Page, the seventeen-year-old elevator operator. There’s no way to know precisely what happened between them, but shortly after Rowland entered the elevator Page screamed.

Understanding the danger, Rowland fled. When questioned by police, Page claimed that Rowland did grab her arm but she did not consider it an assault; she declined to press charges. False accusations that Rowland had assaulted Page, however, spread throughout the larger white community and a manhunt ensued. Rowland was arrested the next day and, due to threats on his life, taken to a secure jail at the county courthouse. In short order, a white mob formed outside.

Black residents from Greenwood feared the worst, and approximately fifty Black men armed themselves and proceeded to the courthouse in the hopes of keeping Rowland safe. By the time they arrived, the crowd of white men had swelled to over a thousand. An altercation broke out when a white man attempted to take a Black man’s gun. The weapon accidentally discharged and within minutes several Black men were lying dead in the street. At dawn the next day, as many as fifteen hundred National Guardsmen, police officers, and the white mob, many of its members having been deputized by the police, streamed through Greenwood, looting and burning Black businesses and homes.

By the time it was all over, three hundred Black citizens had been murdered—some of them shot in the back or burned to death—and the Greenwood neighborhood had been razed. Blacks who survived were placed in internment camps. Thirty-five square blocks had been destroyed and the equivalent of thirty-two million dollars lost. When the smoke cleared, it was as if Greenwood had never existed. For decades, history failed to record that the massacre had happened at all. Newspaper accounts were never transferred to microfilm. Books made no mention of it. Even eyewitnesses kept silent—white participants out of shame, and Black victims out of a desire to spare their children the fear and pain they had experienced.

This was not the first or the last racially motivated mass murder in this country: Black men, women, and children were murdered frequently, usually without consequence to the murderers. In fact, there were thirty-four documented massacres during Reconstruction (1865-1877) and at least twelve between 1908 and 1923, with four in 1919 alone.

What happened in Tulsa, however, was emblematic of the intense racial animosity felt by whites and the backlash Blacks could expect for having the audacity to thrive. On either side of the divide, we carry these holocausts with us in the present and into the future, whether as a victim or—either through identification or unacknowledged benefit—the guilty. The assault on the rights of Black Americans was inexorable, the terror and violence visited upon them unceasing, and the value of what was stolen beyond measure. Yet white America still refuses to acknowledge this dark history let alone the cost to the victims.

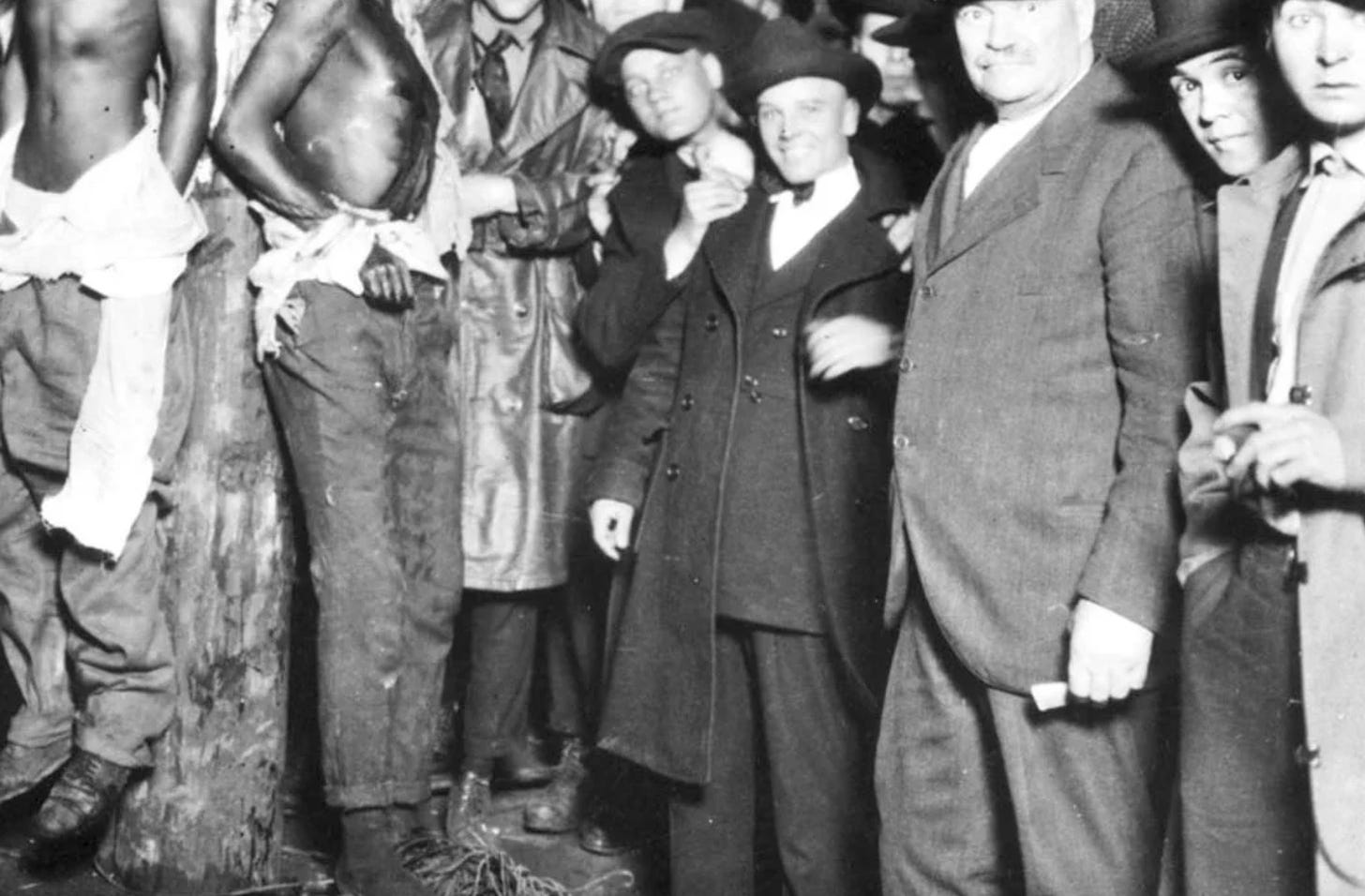

There is no excuse for the behavior of the perpetrators but we need to identify what goes wrong on the individual, intrapersonal, interpersonal, and societal levels that causes people in the privileged majority to behave so monstrously while feeling that their behavior is justified. In many of these cases, but by no means all of them, we know the names of the victims; the perpetrators, however, the ordinary men who committed these barbaric crimes, and the white women who participated in or sanctioned them, suffered no consequences; instead, proud of what they had done or witnessed, they went home to their families, with their gruesome souvenirs, and lived out their lives.

Sometimes the children of these adults accompanied them, witnesses to the monstrosities committed by their parents against other human beings in the name of whiteness, which they were taught to celebrate.

In photographs, whether of lynchings or of scenes of forced school integration, I can’t help but notice the faces of the white children. Some seem confused. Some of their faces are brightened by smiles or contorted with rage and loathing. Not infrequently they look afraid. How many of these children grew up to espouse their parents’ white supremacy? How many, traumatized by violence and the glorification of it, grew up permanently damaged?

Suppressing this history is the best way to make sure white privilege remains unchallenged and racial inequality continues. And that is precisely the agenda of states led by Republican governors, most egregiously Ron DeSantis. White people need to educate themselves in order to avoid another massacre like the massacre in Tulsa over a hundred years ago. The less we know, the more likely it is to happen again.

We must never forget the Tulsa massacre! Yet, this is exactly what DeSantis wants us to do!

Thank you for bringing the Tulsa Massacre to the forefront once again. I am 66, was born in Tulsa and grew up in Dallas and Norman, OK. Graduated from Norman High School in 1975. I never learned about this very sad part of Oklahoma's history until about three years ago. And I took "Oklahoma" history. I will never understand why the massacre was excluded from the curriculum. Makes me incredibly angry at the system.